How 'transference' became central in Freud's psychoanalysis

"Sometimes a cigar is just a... your mother"

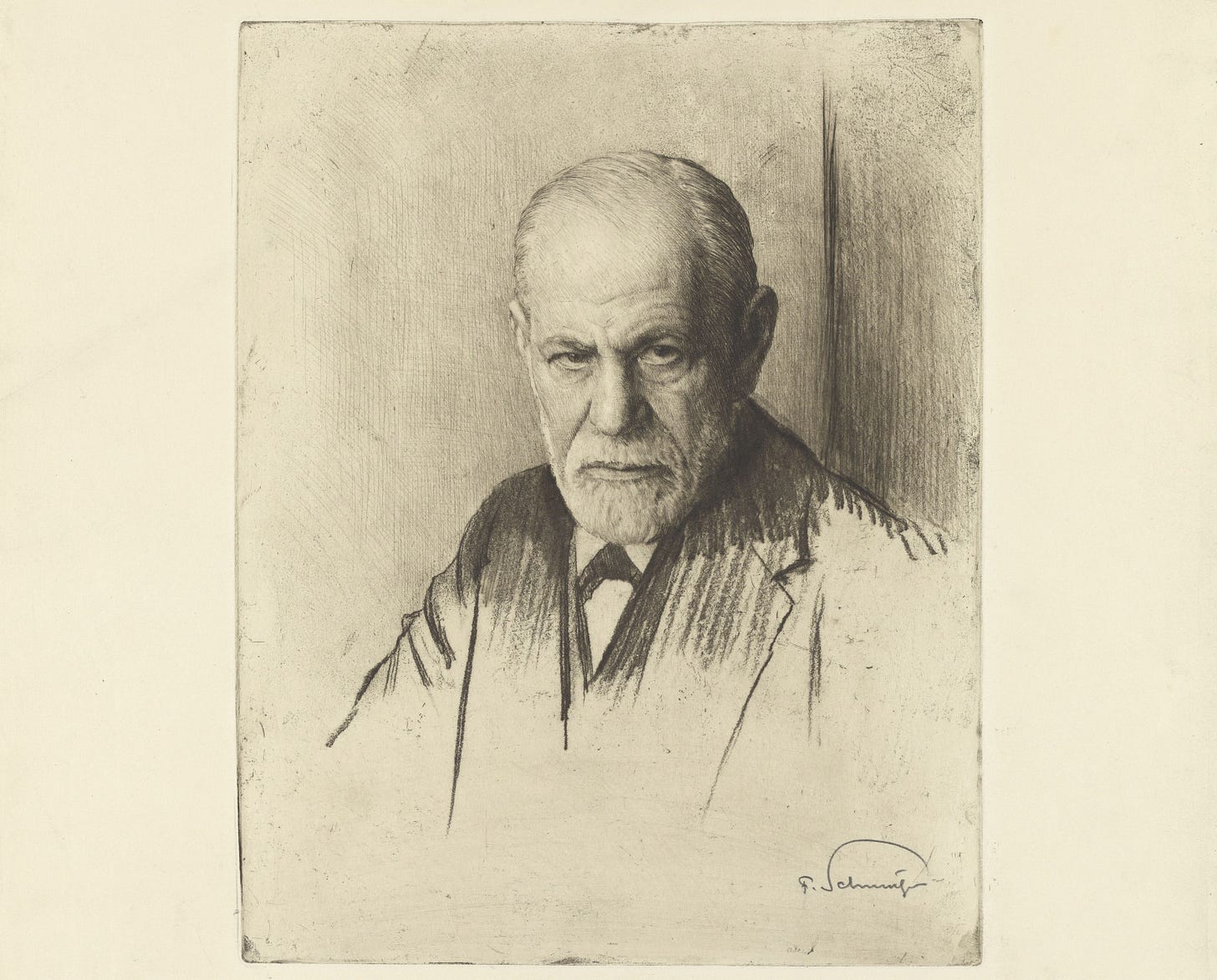

Sigmund Freud's concept of transference stands as one of the most influential developments in the field of psychoanalysis. Initially considered as an interpersonal obstacle, transference evolved over the years to become a central mechanism in psychotherapy.

“A powerful concept, speaking to the essence of the unconscious—the past hidden within the present—and of continuity—the present in continuum with the past” (Schwaber, 2002 cited in Heller, 2005, p.206)

This article explores the concept of transference, its development in Freud's theory, and its significance in psychotherapy.

Transference, as first introduced by Freud in his early work, "Studies on Hysteria," was seen as an obstacle in the relationship between the therapist and the patient (note: in psychoanalytic literature, ‘analyst/analysand’ is more common but here I’ll use ‘therapist/patient’ as transference is relevant across therapeutic approaches, not just psychoanalysis). It manifested as a resistance, a "false connection" hindering the treatment process. Patients often unconsciously projected past desires and conflicts onto the therapist, creating an impasse in the therapy. For instance, a patient might transfer a repressed desire onto the therapist. Freud notes of an example where a patient felt a desire to receive a kiss from Freud, causing a disruption in the treatment. The patient, alarmed at this, was unable to sleep and upon return to therapy could not make progress.

Freud recognised that this instance was not random but rather hinted at specific unconscious impulses. She had felt this desire in the past – for a man to make a bold move and unexpectedly lean in for a kiss, a desire that she had repressed years ago. Upon resolving the transference, it was observed that this desire was transferred into the present moment from the past as a pathological recollection. Having nothing to do with Freud himself, the desire was prompted by the context in which he was the dominant figure of her consciousness, and attached itself to him as if it were a symptom in itself. And so, at once an interference in the treatment, and exactly that which pointed at a resistance which needed to be resolved for treatment to progress.

In "The Interpretation of Dreams," Freud delved deeper into the concept, connecting it with the displacement of affect. He found that transference involved the redirection of unconscious desires onto substitute targets in the preconscious mind. These desires took on different forms, appearing as residues of the previous day's experiences. Transference served as a process that displaced affect, covering up significant unconscious material by disguising it as seemingly insignificant details and so he called them ‘wolves in sheep’s clothing’ highlighting that what appeared as trivial dreams were, in fact, significant unconscious material with valuable insights into the patient's history. In this sense, transference acted as a tool for revealing hidden desires, paving the way for their resolution through analysis.

Freud's most developed understanding of transference came in his analysis of the case of "Dora." The therapeutic relationship had broken down as he had “forgotten to take the precaution of paying attention to the first signs of the transference.” and more importantly, failed to recognise his countertransference onto her. He later realised that transference involved more than specific desires, extending to "a special class of mental structures" (Freud, 1905, p.116). Patients didn't just transfer individual feelings onto the therapist but rather entire frameworks of understanding. In the case of Dora, Freud became entwined in her pre-existing psychological constructions, framing him as representing another man in her life who she was infatuated with. Transference, therefore, was not a mere misinterpretation but a process that allowed the patient to transfer their emotions and perceptions onto the therapist.

"Transference, which seems ordained to be the greatest obstacle to psychoanalysis, becomes its most powerful ally, if its presence can be detected each time and explained to the patient" (Freud, 1905e, p.117)

It became a paradox. It could serve as both a weapon against treatment, by reinforcing resistance, and as a tool for resolution, by bringing hidden material to light. Resolving transference enabled the patient to become aware of what had been concealed, fostering a deeper understanding of their own psyche.

Freud conceptualised transference as a form of resistance, especially when it resulted from the introversion of libido, directing it inward rather than outward, leading to the development of neuroses and pathological processes. This emerged when the analyst became the target of repressed material in the patient, similar to how the patient's own resistance obstructed the surfacing of repressed fantasies. The analyst's role was to reverse this process by bringing unconscious material into consciousness. Transference, despite being a resistance, provided an opportunity for the therapist to use it as a powerful therapeutic instrument. By understanding the unconscious desires behind transferences, the analyst could reveal them, leading to realisation and working-through, ultimately achieving a ‘cure’.

In "Remembering, Repeating, and Working-through," Freud emphasised that transference allowed the analyst to help the patient remember, not condemn, their symptoms. This process involved reconciling forgotten memories, particularly those hidden in screen memories – seemingly insignificant memories that, in fact, displaced significant ones. These forgotten memories, unreachable in the unconscious, found expression through repetitive actions, both in daily life and the analytic setting.

“One cannot overcome an enemy who is absent or not within range” (Freud, 1914, p.152)

Analysis of the transference played a role in curbing the compulsion to repeat, making it instead a motive to remember. By allowing compulsions to be acted out, the analyst revealed the impulses behind them, giving the symptoms a ‘transference meaning’. In this way, the neurosis could be called a transference-neurosis and ultimately cured.

Transference, initially viewed as a minor inconvenience in psychotherapy, has grown into a crucial mechanism in Freud's theory of psychoanalysis. Its development has paralleled the evolution of Freud's understanding of the unconscious and the therapeutic process. It is a powerful tool for uncovering hidden conflicts and desires, enabling the analyst to explore the deepest origins of the patient's pathology, making it a central concept in psychoanalysis. It remains a fundamental element in the success of psychotherapy, allowing the patient to progress from illness to wellness. It is, indeed, a potent instrument for understanding and resolving the past hidden within the present.

You made it this far! Here’s a bonus.

Influential as Freud has been to psychoanalysis, he remains a colourful figure who is immensly documented. Notably, he himself often forgot about transference because of his tendency to overlook his own relationship with his patients. Abram Kardiner, who was analysed by Freud criticised him for this by saying: “The man who had invented the concept of transference did not recognize it when it occurred here.” Kardiner also criticised his fixation with unconscious homosexuality in men, saying that Freud had led him “on a wild-goose chase for years for a problem that did not exist.”

This article was adapted from:

References:

Freud, S. (1895) Studies on Hysteria

Freud, S. (1905) Fragment of an Analysis of a Case of Hysteria

Freud, S. (1912) The Dynamics of Transference.

Heller, S. (2005) Freud A to Z. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Kardiner, A. (1977) My Analysis with Freud: Reminiscences. New York: W. W. Norton.

Strachey, J. (ed.) (1953–1974) The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. London: The Hogarth Press and The Instutute of Psychoanalysis.

Strachey, J. (ed.) (2010) Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams: The Complete and Definitive Text. New York: Basic Books.